Have you seen the controversial Dolce and Gabbana ad the company just pulled from Italy and Spain after protests there?

It is, on the one hand, hardly shocking that a fashion ad is shocking. A lot of fashion advertising (maybe all high-fashion advertising, in fact) depends on the shock of sexual taboo. The implication is, I think, that clothing (fashion clothing, that is) far from being the normalizing or policing force that it often seems to be (wear something right and proper or you will be excluded; no shirt, no shoes, no service) is in fact a site of resistance, of titillating transgression, of freedom. The perversity of fashion is that one fashions oneself (in our culture, one fashions onseself as a unique individual) by adhering to "the fashion" – trends that must be properly read in order to succeed. One is excited by the idea that one is transgressing; one is also excited by the idea that one is being admitted to a community of transgressors. Your private (shameful) sexual excitement at taboo subjects is outed – but also placed in the context of the knowledge that many other people who view this ad will also be excited. It's voyeurism (of the other people who are exited, of the models) and exhibitionism (of your own excitement, of your body, imaginatively clothed in the garments being advertised, imaginatively laid naked in preparation for the clothes being advertised) all in one.

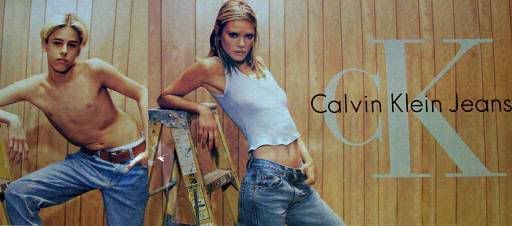

I remember well my fascination with the infamous 1995 Calvin Klein ad campaign. I stared at those pictures for a long time – fascinated, repulsed by my fascination, aroused, confused. I was fifteen – about the age the models seem to be. I coveted their bodies triply: I wanted them; I wanted them as the imagined narrator/photographer/offscreen voice in the t.v. ads wanted them; I wanted to be them, both in their physical beauty and in their desirability to that imagined viewer/maker. He (clearly a he, a carnivorous, bisexual, devouring he) made them. He made them famous, he made them beautiful, he made them sexual, he made their bodies. "He," then, becomes the force of fashion itself – dangerous, violent, unstoppably desiring and desirable, hailing me, the viewer, as both a victim, like the models, and a pederast, like the photographer. Fashion is equated with desire, desire with that which is totally forbidden, that which is forbidden with that which creates.

I remember well my fascination with the infamous 1995 Calvin Klein ad campaign. I stared at those pictures for a long time – fascinated, repulsed by my fascination, aroused, confused. I was fifteen – about the age the models seem to be. I coveted their bodies triply: I wanted them; I wanted them as the imagined narrator/photographer/offscreen voice in the t.v. ads wanted them; I wanted to be them, both in their physical beauty and in their desirability to that imagined viewer/maker. He (clearly a he, a carnivorous, bisexual, devouring he) made them. He made them famous, he made them beautiful, he made them sexual, he made their bodies. "He," then, becomes the force of fashion itself – dangerous, violent, unstoppably desiring and desirable, hailing me, the viewer, as both a victim, like the models, and a pederast, like the photographer. Fashion is equated with desire, desire with that which is totally forbidden, that which is forbidden with that which creates. How much of that did I understand at the time? Not too much. I only know I felt both desire and shame, and it was puzzling, and it was interesting too. At the time I couldn't decide whether I thought the ads were immoral or not. I am against pedophilia, but I am for freedom of speech; I am against the legitimizing of hurtful passions, but I am also against pretending that they do not exist. I eventually came down on the side of some sort of early understanding of the return of the repressed: these things will out, and then you put them back in – but that doesn't stop them from coming back out again some time in the future.

Now, of course, I'm a more informed reader. I've learned tools, both through literary study and through life experience, that help me decode the power that was at work on and in me when I considered those pictures. As a more conscious viewer, I can ask informed questions of my responses – what is it, precisely that excites me? What is it that repells me? How much is that repelling part of the ad, and how much is it part of social discourse surrounding the ad? How does this ad approach male and female viewers differently? How much does it participate in the construction of the body and desire as diseased and disease-making? How does it fit into the aims of capitalism and how does it switch commodity fetishism with sexual fetishism? What about this ad speaks particularly to its historical and cultural moment?

But I also, as a more informed reader, may simply be abstracting the power enacted by the ad, not resisting it. I have different terms to describe my subject position – that doesn't mean I'm not not still a subject being constructed, being hailed by the social/capitalistic/sexual forces behind the pictures. I also have a dark suspicion that one thing I've done is simply to legitimate the arousal I feel at admittedly pedophilic images by saying "the pedophilia and the arousal are both part of the construction of Self under Fashion." In other words, instead of really interrogating a troubling and socially negative experience, I've just obscured its negativity. What purports to be clarification may really be mystification of another sort.

Even if that's all true, though, I'm still in a different position viewing the Dolce and Gabbana ad than I was viewing the Calvin Klein ones twelve years ago. I feel similar, though. My first thought, on viewing the ad, was "god that's hot." I find it, admittedly, erotic. It's supposed to be, of course, and it works – the ad evokes both the eroticism of the woman's body (her coloring, in fact, makes her seem almost like an alternate self for me – I wonder if that's behind the choice of a dark-haired model. Brunettes perhaps seem closer to "real" women than blonde models, who are so often associated with ideals, do. She also, of course evokes Bettie Page.) and the eroticism of the rape fantasy.

Rape fantasy, of course, is another piece of American sexuality that, like pedophilia, is so intensely common that its sublimation is almost not sublimated at all. The idea of rape as erotic is everywhere – and is everywhere derided. My second thought was "god that's wrong." I described the ad to Jamie, and then described my thought process, and she said "that's exactly what went through my head! I thought 'that sounds hot!' and then I thought 'uh-oh.'"

But there's something about the context of this particular rape fantasy that makes it even more interesting. When I first viewed the ad, without reading the text, I thought "well, this is such a common fantasy, such a common part of the depiction of female sexuality as inseparable from the fetishism of dominance/submission, that I'm surprised it raised a fuss. I don't think I find it unacceptable, though I perhaps find the ubiquity of this type of sexuality distressing or worth questioning." But then I read that the picture had originally appeared in Esquire, and it changed my thinking dramatically.

Because, see, if this had been an ad in Vogue, I would have no problem with it. But an ad in Esquire? No, that's not okay. That's beyond the political pale. Rape fantasy for women is, as I say, nearly ubiquitous. Rape fantasy as a technique to sell to men? Now, that is something really transgressive, and perhaps really morally unsavory. What's being sold here is not the idea that fashion, like sexuality, gives women the experience of being controlled and desired at the same time it (violently) makes them desirable. What's being sold here is the idea that fashion, like the phallus, gives men the power to violate, to control against the will of the controlled. The difference is, of course, subtle – and both "stories" I've told about the ad are present within it (since they're both present in hypothetical readers). But one story is descriptive, the other proscriptive – the perlocution of this illocution, to use Austinian terms, changes markedly depending on the magazine in which it's printed (integral to the total speech situation).

So what do we do with this type of speech? (I'm considering the ad to be speech, in a generalized, language theory, freedom-of-speech kind of way.) Is it in fact okay? How does my feeling that it's beyond the pale to advertise this way to men tally with my belief in freedom of erotic imagination? Is this representation harmful, or can it be construed as harmful? What does this particular type of "exploitation" – the exploitation of fantasy – do?

It's all fascinating. I'm definitely going to keep thinking about it. These questions come up in my Antony and Cleopatra paper, and I think I'll write my Critical Methods paper on the D&G ad (and the critical theory surrounding transgression and containment that I've been obliquely and perhaps ineptly drawing on throughout this post). In fact, I suspect these questions are one of the potential real-life ramifications of the dissertation that's hazily, slowly, confusingly taking shape in my mind and my writing.

One thing I'll definitely want to do: close readings of both ads and justification of why close reading can help me here. For example, the backgrounds: There's a marked difference between that wood paneling (which evokes a really vivid erotic fantasy and a physical, locational, understanding – basement movie studio; anonymous suburb; the decline of wholesome america) and the weird cloud and box background of the d&g ad (a late-added mitigating feature? An attempt to signify fantasy, as if fantasy were less harmful than "movie studio?")

It's all so cool. Man, this is why I love what I do.

Labels: bodies, feminism, morality, queer, representation

How goes it my dear Ginny, its Jay Knowlton, up in Maryland seeing how you were doing :)